In the Government’s recent Levelling Up White Paper it set out 12 missions. One of these is:

By 2030, pay, employment and productivity will have risen in every area of the UK, with each containing a globally competitive city, with the gap between the top performing and other areas closing.

In a recent article the Centre for Cities put forward two criteria for a globally competitive city. There approach uses data from the OECD on metropolitan areas, thereby allowing us to readily compare across 700 cities from around the world. The Centre for Cities suggest two basic criteria for a globally competitive city: (i) A population above 950,000 people, and (ii) productivity per worker above $95,000 (at constant prices and purchasing power parity with a base year of 2015). On these criteria the UK has only one globally competitive city – London. By contrast, Germany has eight and France has five. Based on their analysis, the Centre for Cities propose that Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow have the highest likelihood of becoming globally competitive cities. But what about Derby, Leicester and/or Nottingham?

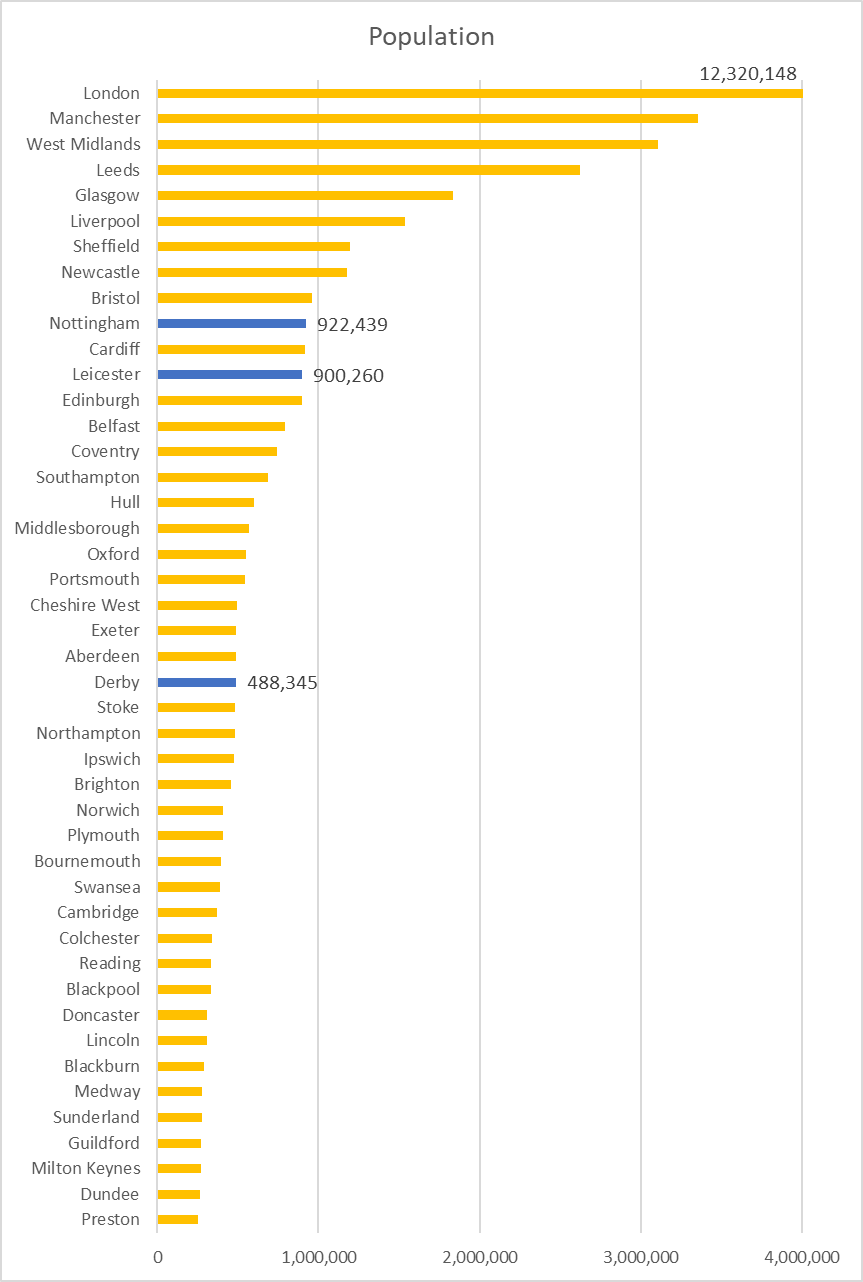

Let us look first at population size. In doing so it is worth explaining that the OECD uses a definition of functional urban area that ‘encompass the economic and functional extent of cities based on daily people’s movements’. On this definition Leicester extends well beyond the Leicester City Local Authority area to cover Blaby, Oadby, Wigston, Charnwood etc. Thus, while Leicester, as defined by the City Council area, is home to an estimated 350,000 the Leicester urban area is home to many more. The chart below summarizes population for the UK areas available on the OECD database. You can see that Nottingham and Leicester just fall below the 950,000 threshold suggested by the Centre for Cities. Given, however, that the East Midlands is predicted to see fast population growth over the next few decades this would seem no reason to rule them out. Derby, by contrast, seems to be ‘out of the running’ in terms of population size.

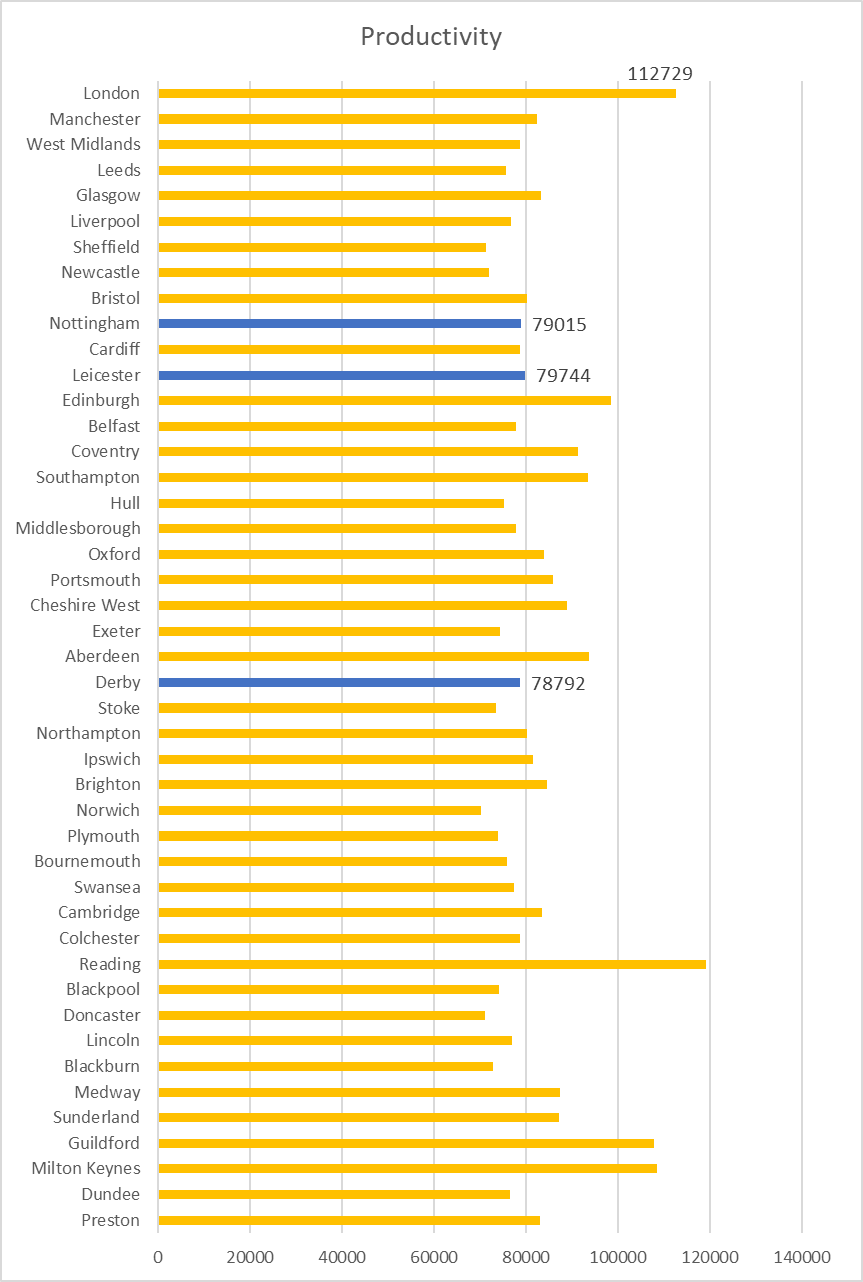

Let us look next at productivity. The chart below summarizes productivity per worker ($/year) for cities ordered by population size. There are a handful of urban areas in the UK that meet the $95,000 threshold – Milton Keynes, Edinburgh, Guildford, Reading and London. Of these, only London and Edinburgh match and nearly match the population threshold. Clearly, therefore, the move towards globally competitive cities is going to need a fairly seismic shift in productivity to address the productivity puzzle. Nottingham and Leicester seem on a par with other candidates, e.g. Cardiff, Bristol, Liverpool, in terms of their ‘starting position’.

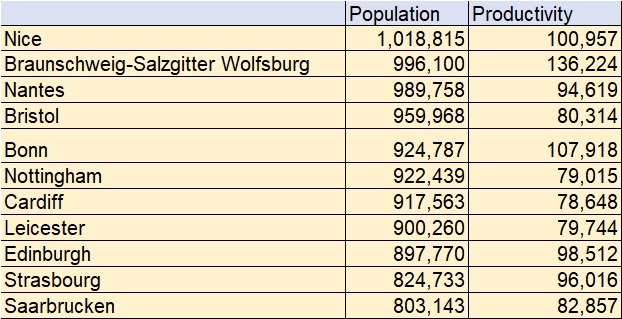

To illustrate the potential for Leicester and Nottingham we looked at ‘comparator cities’ in France and Germany. The table below lists all the cities in a population range between approximately 800,000 and 1 million. Comparisons with Nice or Bonn would seem strange given their particular location and historical characteristics, respectively. The comparison with Braunschweig, Nantes and Strasbourg seem more apt in terms of what could be possible. For instance, Braunschweig has become one of Germany’s most dynamic, R&D intensive cities with a strong manufacturing base.

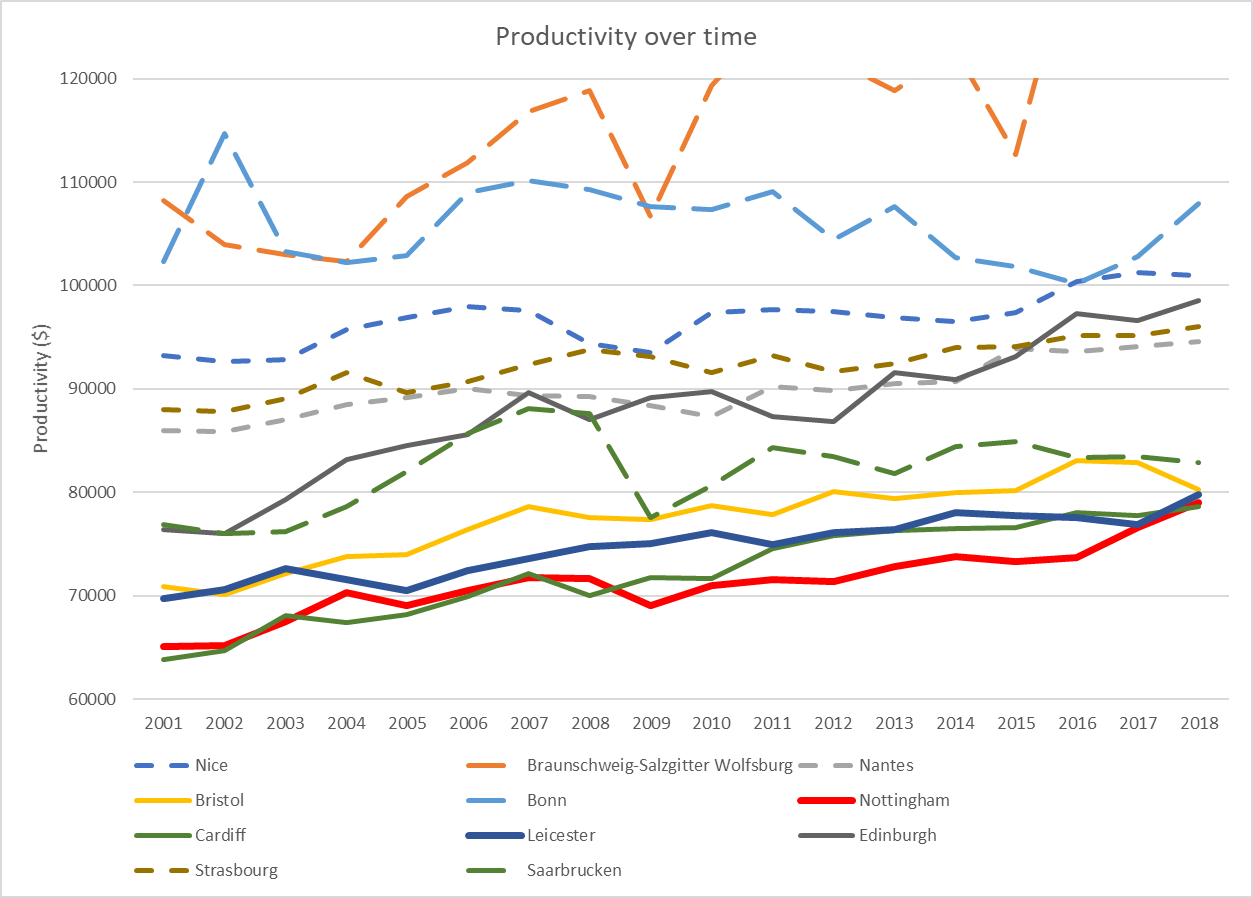

In our final chart we plot productivity over time across the cities identified above. You can see that in the German and French cities, with the exception of Braunschweig, productivity growth has largely stalled – albeit at a higher level than in the UK. In the UK cities, by contrast, productivity is increasing. Edinburgh has made the transition above the $95,000 productivity threshold. Nottingham and Leicester are still a long way from the threshold but on an upward trend, and similar to Cardiff and Bristol.

The final thing we would emphasize is that East Midlands has been starved of investment over recent decades. This quote from East Midlands Councils illustrates the problem:

If the East Midlands was funded to a level equivalent to the UK average, over the 3 years since 2017, the region would have benefited from an extra £3.5bn of funding for ‘economic affairs’, or £2.5bn if matched to the levels of the West Midlands; and similarly, the region would have an extra £1 billion a year to spend on transport if funded at a level equivalent to the UK average.

If the East Midlands were to be given more investment then we would surely see increases in productivity and growth. It would seem, therefore, that Leicester and Nottingham are ideal candidates to become globally competitive cities. This is not to say that boosting productivity is easy, because it is not. But, of all the cities in the UK that could be targeted to make the transition, it seems that Leicester and Nottingham offer real potential,