Ahead of its annual party conference, the Conservative government has argued that the supply chain disruptions and labour market shortages we are seeing because of Brexit will ultimately help increase wages and productivity as the UK moves away from a reliance on cheap labour. Indeed, there are claims it is already working. In a recent BBC interview Prime Minister Johnson said “What you’re seeing is finally growth in wages, after more than 10 years of flat-lining what you’re seeing is people on low incomes being paid more.” This view was subsequently echoed by Chancellor Sunak. A rise in productivity and wages would, indeed, be welcome. But, is there any sign of it actually happening? Here is my view, an extended version of an article initially published in Central Bylines.

Watching the statistics

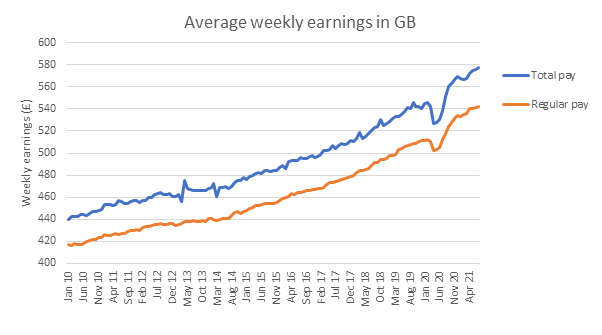

Let us start by looking at the latest Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates of average weekly earnings for regular pay and total pay (including bonuses). The chart below plots average earnings since 2010.

As you can see, nominal wages have been growing steadily over the last 10 years. The obvious blip is a drop in wages during 2020 because of the impact of Covid-19. This drop is crucial when it comes to interpreting statistics on wage growth. For instance, total pay has grown by nearly 10%, and regular pay by nearly 8%, since the low point of April 2020. That, however, is something of a statistical anomaly because it comes after a sharp drop in wages. A fairer comparison is to look back to say January 2020, before Covid-19 hit the UK economy. Since then both weekly and regular earnings have grown by 6%.

At first glance 6% may seem an impressive rate of earnings growth over an 18 month period in which the UK has suffered from a global pandemic. There is also evidence that growth was highest for those on lowest incomes. Was, therefore, Mr Johnson justified in singing the praises of his government?

Reasons to be cautious

There are several reasons to be cautious. First, the Covid-19 pandemic has led to a significant fall in employment which is still 200,000 below the pre-pandemic level. Those on low wages were particularly at risk of unemployment during the pandemic because, for instance, they could not work from home. This can create what is called a compositional effect whereby an ‘artificial’ rise in recorded earnings results from low earning workers dropping out of the sample. So it is not that anyone is earning more, it is just that the statisticians are no longer counting some low earners who have become unemployed. The ONS estimates that once we account for the compositional effect and the previous drop in earnings the latest headline growth rate of regular earnings drops from a reported 6.6% to between 3.2% and 4.4%. The Bank of England has similar estimates which would imply the growth in average wages since January 2020 is only 3.6%.

A second crucial factor to consider is prices. Here, again, we encounter several complicating factors. For instance, the Government’s Eat Out to Help Out Scheme lowered prices which are now rebounding, creating an ‘artificial’ shift in the inflation numbers. But in terms of the raw numbers prices as measured by the Consumer Price Index Including Owner Occupied Housing Costs (CPIIH) have risen by 2.8% since January 2020.

A 3 to 6% rise in nominal earnings against a 2.8% rise in prices means that Mr Johnson can legitimately claim there is evidence that real earnings have risen. With large uncertainty about both the earnings and price data this evidence, however, is tenuous at best. Indeed the ONS emphasise that “at this time [we] feel it important to explain to users that there are different effects that mean our statistics need to be interpreted with caution.’’ This is a view echoed by the Bank of England.

In short, it is far too early to judge which way real earnings are moving. The best one can realistically argue is that wage growth has held up better during the pandemic than widely feared.

Levelling up?

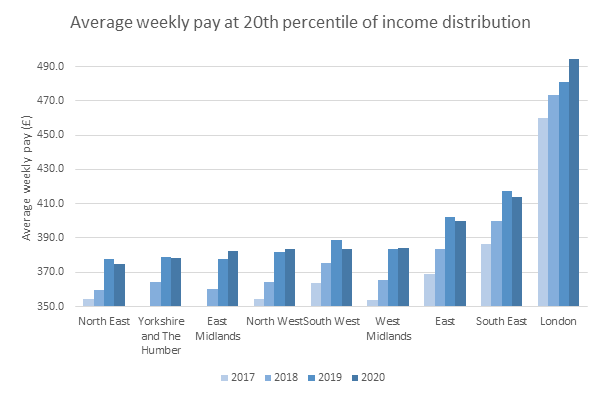

The focus on earnings and wages is driven in large part by the debate on levelling up. So let us look at trends in low pay in the regions. In the chart below we plot the average weekly pay by region of those at the 20th percentile in the income distribution. This is a measure of pay at the lower end of the income distribution. The last publicly available data is for April 2020 but shows the scale of the problem.

You can see that pay in London is relatively high and on a clear upward trajectory. By contrast, pay in the Midlands and North was static or falling as the pandemic hit. There is little here to suggest any levelling up. It would be a surprise if that situation has fundamentally changed over the last 18 months, particularly given that the economic impact of the pandemic was strongest in the Midlands and North.

Going forward

Looking to the future, in their latest Monetary Policy Report the Bank of England predicts a transient rise in inflation due to “higher energy and goods prices, which in turn reflect rising commodity prices, transportation bottlenecks, constraints on production, and strong global demand for goods”. They also predict that wage growth will remain strong at around 4% due to a tight labour market. Whether or not earnings will outpace prices is therefore unclear. There is, though, no indication of the sustained rise in low wages that Mr Johnson is keen to promote. The Midlands and the North have structural problems, such as low skills and low productivity that are not easily fixed. And are definitely not going to be fixed by people retraining as lorry drivers or poultry workers. Indeed the economic drag of Brexit will likely make levelling up far more difficult because the UKs regions are predicted to suffer most.

Clutching at straws

Has there been an increase in wages for the poor? While Mr Johnson can point to some very tenuous evidence that real wages have increased over the last 18 months this really does seem to be a desperate clutching at straws. An economy struggling with the consequences of Brexit and a global pandemic is highly unlikely to produce a telling increase in real wages, particularly for those on lower incomes.